C is for Crafting your Story (dramatic arc)

I briefly touched on the basics of storytelling yesterday and today’s post with expand on that and provide some links I hope you’ll find useful.

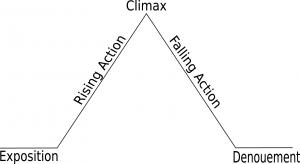

Each story you write will follow a structure similar to the image pictured below:

This is Freytag’s pyramid, (named after German novelist, Gustav Freytag), and is modified from the structure Aristotle discussed in Poetics. Aristotle decribed the dramatic structure (arc) of a story as being a triangle, but Freytag added two further levels of analysis – rising and falling action – and the triangle became a pyramid.

Most stories follow this basic form, whether it is a short story, a novel, or a screenplay, and it comes in many guises:

- Three-act structure

- Five-act structure

- Six-act structure

There is a variety of these numbered structures out there(see the links for ‘beat sheets’ for futher information on this), some with more ‘steps’ than others, but the basics remain the same — give your character(s) a goal, throw every obstacle possible in their path, and then watch them suffer as they step ever closer to the biggest obstacle of all – the climax.

There are websites out there that delve deeper into this (I’ll post links at the end of this post). Personally, I think it can over-complicate things if followed rigidly, but if the first half a book is devoted to exposition (description/world building), you’re going to end up with a pacing issue. I had the misfortune of reading a book that did this (an indie book which I won’t name). The cover was eye-catching, the blurb was engaging, but it was like reading a manual about a subject the author was clearly passionate about. I stuck with it purely to find out ‘where’ the story started (page 121). The first one hundred and twenty pages were devoted to exposition (and don’t get me started on the five-star reviews raving about the fast-paced action).

So, the basic dramatic arc is as follows:

- Exposition

- Rising Action

- Climax

- Falling Action

- Denouement

If you think back to any book you’ve read, or film you’ve watched, you’ll usually find that it begins with an introduction to your main character(s), the setting, the problem(s) they face, and their motives. This is your exposition.

For example:

You introduce Bob to your reader, explain how he ended up on the wrong space station and that if he doesn’t get to the right one – and quickly – the whole world as we know it is going to blow up.

Your rising action might include communications breaking down (it’s an old space station, after all) the shuttle unlocking and returning to Earth on autopilot before he realised what was happening, oh, and there’s the teensy matter of his air running out (dodgy valve).

The climax is the biggest conflict of all. Bob is a skilled technician. Fixing the communications and the air dodgy valve was easy (if a little hair-raising at one point), but after talking to ‘base’, the earliest they can turn the shuttle around is a week next Tuesday – ten days after he needs it. He has to improvise. As luck would have it, there’s a tin bucket of a craft in the hanger. It works – just – but it has a mind of its own where the steering is concerned (and this is beyond Bob’s skillset to fix). He might be flying to his death, but he’s going to die if he stays in the old space station because if the Earth goes bang, there’ll be no one left to rescue him.

Will he succeed in his mission? Will he die? Personally, at this point, I think it’s wise to allow him to live, but solely for the purposes of providing the reader with a dramatic climax.

The falling action follows the climax. The main conflicts have been resolved. Bob made it to the correct space station by the skin of his teeth (cliche phrase, I know, but it works) and with seconds to spare. He entered the kill code to counteract the threat to Earth and now all he has to do is wait for his ‘bus’ home.

The denouement is the end of your story and where any loose ends can be tied up. In this story, Bob makes it home to Earth and is reunited with his family. He vows that this time he really is retiring from the space agency – no matter how much money they offer him to save the planet.

This is the point I like to put a twist in that I have foreshadowed and hope it will drop the reader’s jaw open. As I’m a ‘pantser’ and can only think things up while writing, I’m unable to offer one right now. Maybe when I have more time I’ll make this into a short story and you can see what I mean.

The dramatic arc within scene and chapters.

I don’t know if you noticed what I did while explaining exposition, but I’ll copy and paste it again here, as my wording was intentional (before I got sidetracked with detailing Bob’s strife).

‘You introduce Bob to your reader, explain how he ended up on the wrong space station and that if he doesn’t get to the right one – and quickly – the whole world as we know it is going to blow up.’

There are different ways of starting a story and authors these days are advised to start in medias res – at the point of action. Gone are the days where pages and pages and even more pages of explanation, description, and worldbuilding were the norm – stories tend to jump into the midst of battle (or close to it).

The reader isn’t going to give two hoots if I open the story with Bob’s life history. I could tell them how long Bob worked for the space agency, or how he fought to get his engineering degree while holding down three jobs, or that it was pure grit and determination that saw him rise through the ‘ranks’ to chief engineer. I could tell them how he is the most qualified for the job and blah blah blah… boring.

What the reader wants to know when opening a story is:

- What is happening now?

- Who is the main character?

- Where are they?

- What is the problem?

- How are they going to dig themselves out of this mess?

And in the example given above:

- What do you mean they sent him to the wrong space station?

Many a client has received my ‘first chapter’ spiel, in which I advise that there is such a small window of opportunity to not only grab hold of a new reader’s attention but to keep it. The first line, paragraph, page, and indeed, the first chapter, all play a key role in this. You may even be wondering how you’re supposed to inform the reader about the character, setting, stakes, motives etc while not filling your first few pages with exposition (a question I asked myself many a time in my early days of writing).

One answer to this is the A, B, D, C, D:

- A: Action

- B: Background

- D: Development

- C: Conflict/Climax

- E: Ending[divider]

This method is credited to Anne Lamott, an American author and university professor. I follow this structure (sub-consciously) while writing. I don’t have an ending in each chapter, but I do try and end on a mini-climax.

Let’s go back to Bob (and this isn’t my best writing – it’s a first draft):

Bob stepped through the airlock and whistled. (Action) A rickety looking interior wasn’t something he associated with Space Station Ex, though it had been a while since his last visit (Background). He secured his helmet and half bounced, half floated along the narrow corridor to the main console room. He tutted upon discovering it was in sheer darkness. Control could have warmed it up remotely. It wasn’t like they didn’t have eight hours notice that he was on the way.

He dug his torch out of his pocket and located the switch to power up the generator. (Action) It groaned and spurted before settling into a strained hum. Bob settled into one of the chairs and fired up the communications. Control knew he was here, but procedure dictated he call in and let them know he’d arrived. Once that was out the way there was a sachet of microwaved tea with his name on it. (Development).

He thumped the top of the comm unit. It flickered before fizzling out with a distinct pop.

He leaned back in the chair with a muttered curse, and then floated back out of it almost immediately, pressing his nose to the window. Space Station Ex – his intended destination – stared back at him (conflict).

“You have got to be kidding me!”

What I have tried to do in this example of A, B, D, C, E, is inform the reader of certain facts without saying it directly:

- Introducing my main character (Bob) through action (he’s walking through the airlock, thus announcing his arrival. The second sentence tells us where he is).

- I’ve informed the reader (through narrative ‘voice’) that the space station isn’t how he envisioned it looking, and also that he’s been to space station Ex before.

- I have tried to put some foreshadowing in place (the payoff for which will come later) by describing a rickety looking interior, a struggling generator, and I went ahead and broke the communications (the flicker and pop).

- Finally, I had Bob notice something out the window as he sat back to contemplate the broken comms, and as he looks out of the window, he sees the space station he ‘should’ be on staring back at him.

I haven’t strictly followed the formula as I have action, background, development, action, background, development, conflict, but I hope it is an example of how to layer information and feed it to the reader while moving the story forward.

I’ll end this post here as I could talk about this all day long, but as a final note, part of writing is about discovering the methods that work for you. Don’t take what I say as the ‘only’ way to write.

Useful links:

Books:

This ultimate insider’s guide reveals the secrets that none dare admit, told by a show biz veteran who’s proven that you can sell your script if you can save the cat!

*Although this is a screenwriting book, the information on the 15 point beat street is interesting reading and shows examples of well-known films beat sheets. The associated website can be found here: http://www.savethecat.com/todays-blog/how-the-beats-helped-a-writer-self-publish-an-amazon-hit

In the multi-award-winning Structuring Your Novel, Weiland showed writers how to use a strong three-act structure to build a story with the greatest possible impact on readers. Now it’s time to take that knowledge to the next level.

*FREE ebook*.

K.M. Weiland’s website can be found here: https://www.helpingwritersbecomeauthors.com/

Trackbacks/Pingbacks